Introduction:

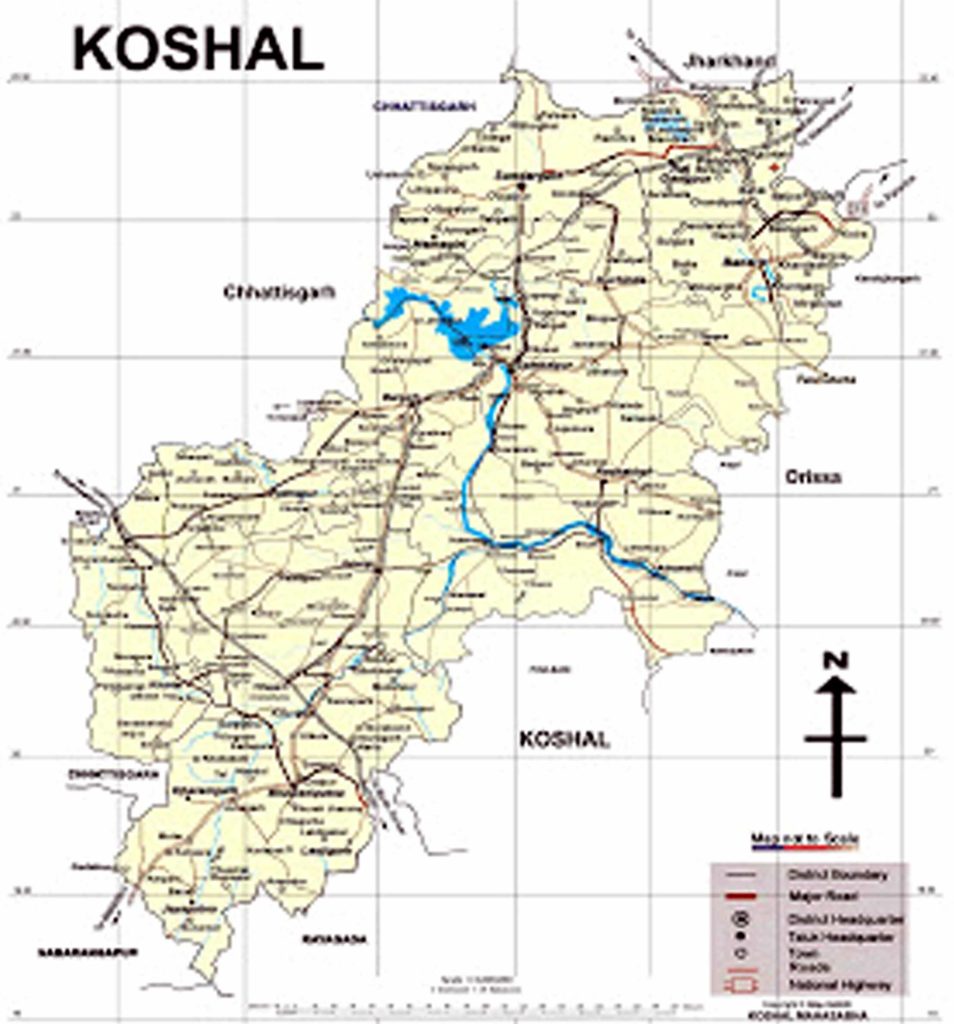

‘Western Odisha’ once upon a time, formed a part of the ancient Koshal kingdom having its distinctive history, culture and unique salient features. The proponents of the separate Koshal state movement which is going on in the western part of Odisha have been mobilizing people and spearheading their movement along such a historic path so as to bring back their golden past and to preserve, protect and promote their rich cultural heritage. The people of western Odisha living in as many as eleven different districts not only ascertain their common ancestry but also share their common fate of being backward and underdeveloped due to “internal colonialism” including state apathy and “coastal conspiracy”. Nevertheless, they are struggling and mobilizing forcefully to deconstruct their stigmatized identity and asserting today a unique “Kosli identity”, which is increasingly being recognized world over. And it is this “Kosli identity”— which the leaders of the Koshal movement are using to garner people’s support and galvanize Kosli consciousness and “Kosli nationalism” — the emblematic chord of the demand for a separate Kosal state. It is, therefore, that we discuss in the present article, some of the significant markers of what constitute Kosli identity in terms of a) Kosli language and literature and b) Kosli culture.

Kosli – Sambalpuri Language and Literature:

The language spoken by people in the western part of Odisha is known to be Kosli or Sambalpuri as against the Kataki, which is meant for the dominant standardized and official version of Odia. This language is spoken and used in day to day life by people in the ten districts of western Odisha and Athamallik Sub-Division of Angul District numbering about 1 crore spread about more than 50,000 sq. K.M.[1] ‘Western Odisha’, in common parlance, refers to the four undivided districts of Kalahandi, Bolangir, Sambalpur and Sundargarh. Recognizing their common culture and common fate of being poor, backward and underdeveloped, the Government of Orissa constituted a special agency for their “accelerated development and advancement” which is known as ‘Western Odisha Development Council’ (WODC).[2] The four (4) Districts comprising the area of the Council, as a consequence of reorganization of Districts in Orissa in 1993 now consist of Kalahandi, Nuapada, Bolangir, Subarnapur, Sambalpur, Bargarh, Deogarh, Jharsuguda and Sundargarh districts.[3] However, after people from Boudh and Athamallik Sub-Division of Angul District appealed and demanded for their inclusion in the special programme, the jurisdiction of “Western Odisha” has been extended to eleven (11) areas/zones[4]. Nevertheless, the whole of this Western Odisha region is found to subscribe to a common socio-cultural milieu. “Culture” seen as a broad term, comprises of tradition, rituals, festivals, language, life-style, food pattern etc. Or more suitably to bring in the classic definition of E. B Tylor, the celebrated cultural anthropologist, “culture… is that complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, arts, morals, law, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by a human as a member of society”.[5] It is, therefore, that an understanding and appreciation of the culture of a particular region warrants a proper analysis of its historical geography and the changes that take place across time and over space. Needless to mention here that as regards Odisha or for that matter Western Odisha, we have not come across any detailed study of the ‘culture-complex’[6] i.e., a group of cultural traits all interrelated to each other which constitutes a representative culture of a particular people, community, nation and region, particularly with regard to its historical geography. The language and literature has not been studied properly until recently. This is due to the misunderstanding that the language of this region has been considered to be a mere ‘dialect’ of Odia language spoken and written by the dominant people of coastal Odisha including the state capital. Although during the Odia Language Movement and the state formation of Orissa province, much has been contributed by the people of the region, their contributions have neither been recognized nor have been written about as a part of standard Odishan history. It is only very recently that somehow their significant contributions have come to our knowledge and limelight due to efforts made by some researchers, historians and activists of the Koshal movement.[7] Needless to mention that among the many districts forming part of the Central Provinces during the British period, only the District of Sambalpur was an Oriya-speaking tract which had lost its independence in 1849 after the sad demise of the last Chauhan King Raja Narayan Singh.[8] It is noteworthy to mention here that all the lowest personnel of the British government were mostly Hindi-speaking non-Oriyas. The British rulers did not understand any language other than Hindi and they also instructed the lower personnels not to pay any importance to Oriya language. And it was in 1895 that the then Chief Commissioner of Central Provinces, Sir John Woodburne passed an Order directing that Hindi shall be the language of Courts and Government Offices in Sambalpur.[9] In sharp reaction to this Order, people in the region under the leadership of Dharanidhar Mishra mobilized themselves and in a meeting held on 13th June 1895 passed a resolution opposing such an imposition of Hindi language in the area.[10] They not only submitted a Memorandum to the then Vice Roy Lord Elgin, but spearheaded the movement for its resolution. Appeals were made to people all over the Oriya speaking tract and nationalist writings were written in and published by several dedicated intellectuals of the region in the pages of Sambalpur Hiteisini and Hirakhand.[11] The intellectuals of the region rather galvanized their movement further following the census of 1901. In a well-documented Odia book entitled Simla Yatra i.e., Journey to Simla,[12] we come to know that five eminent persons of the region namely Mahant Behari Das, Balabhadra Suar, Braja Mohan Pattanaik, Madan Mohan Mishra and Sripati Mishra had decided to proceed to Simla so as to meet the Viceroy Lord Curzon in September 1901 and to apprise of their demand that Oriya language shuld not only be introduced in the region but also that an area in which a particular language like Oriya was the medium of instruction, should be placed under one homogeneous administration. It is further reported that although the delegation from the region could not meet the Viceroy in Simla, later on, the Chief Commissioner of Central Provinces Sir Andrew Fraser, came to Sambalpur and finally from 1903 onwards Oriya was introduced as the official language in the Courts and government offices in the region. Another crusader of the movement from the region was the well-known poet Ganga Dhar Meher[13], who not only spread consciousness among Oriya-speaking people to wake up and get united to claim their mother tongue as against Hindi or Bengali which were imposed upon the Oriyas, but also liaisoned with the British authorities to consider such a genuine cause. When Oriya language was in crisis, it was Meher who proved to be one of the stalwarts who had the courage to herald a renaissance in Oriya language and literature. In fact, Meher was so passionate and spirited and determined to promote the Oriya language movement of his time and reinstate the glory of his language, literature and culture that he went to the extent of suggesting that one who does not love and respect one’s motherland and one’s mother tongue can never ever be considered as an educated person. This can be best summed up in his very famous and most popular poem.[14] Not only this, but there were numerous others who put their head and heart and struggled tooth and nail for Oriya language and an independent province of Orissa. It may also be recalled here that from the very first conference of Utkal Union or Utkala Sammilani in 1903 till the formation of the State of Orissa the people of the region contributed significantly. [15] However, once the state was finally formed in 1936, the leaders and intellectuals-scholars of Orissa forgot their contributions and rather looked down upon those who spoke languages other than the dominant Odia language.[16] In fact, almost every person I talked to during my field work who were exposed to friends, relatives or officials or even by chance encounter to people from coastal Odisha, they had bitter experience of having been laughed at or joked at for their language, literature and culture. This has been polarizing day by day. And the result has given birth to such a situation, to which linguists call “diglossia”, i.e., when people of this region speak their language/dialect as a vernacular in their everyday life, but they have to turn to “standard/official” Odia language as a medium of education in schools and colleges and for any other public-official purposes. The irony of the situation is that the vocabulary of Kosli-Sambalpuri language consists of numerous words and phrases which are unintelligible to people in the coastal region. It is, therefore, argued that there is an intrinsic – fundamental difference between Kosli-Sambalpuri language vis-à-vis language used by people from coastal Odisha.[17] As a matter of fact, people from western Odisha have already submitted a number of memoranda over the period, to the Government of India so as to include Kosli language in the 8th Schedule of Indian Constitution, which lists the government recognized official languages.[18] Although initially the inclusion of a language in the Schedule meant that the language would be one of the bases that would be drawn upon to enrich Hindi, today, the list has acquired more significance. The Government of India is now under an obligation to take suitable measures for the development of these languages, such that they grow rapidly in richness and become effective means of communicating modern knowledge. In addition, a candidate appearing in an examination conducted by the Public Service Commission is entitled to use any of these languages as the medium in which he or she answers the paper. Thus, inclusion of a particular language in the Schedule provides certain specific advantages to its speakers which will be denied to them if it is not included in the Schedule. As regards Kosli/Sambalpuri language, the Chief Minister of Odisha Mr. Naveen Patnaik has already recommended the case and requested the Centre to include in the Schedule. However, it is needless to mention here that there are certain people especially belonging to coastal Odisha who are protesting and resisting such a move tooth and nail. One of the staunch critiques of the proposal has been Dr. Debi Prasanna Pattanayak, who has been a Professor and a well-known linguist and the Founder-Director of the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL), Mysore. It also needs to be underlined that it was Dr. Pattanayak, who was awarded the Padma Shri in 1987 for his contribution to formalizing and adding Bodo as a language in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution and who was instrumental in getting classical language status for Odia but is now so vehemently opposing for inclusion of Kosli/Sambalpuri language in the Schedule.[19] He looks down upon the advantages to the people of the region if it is included in the Schedule. Rather than appreciating such a move by the marginalized and stigmatized millions, his main apprehension has been that once the language is included in the Schedule, it will subsequently result in bifurcation of the state—on the basis of linguistic division.

It may be noted here that the literature in Kosli-Sambalpuri language has been flourishing day by day. There are already volumes of literature available in almost every literary genre such as poetry, prose, essay, critiques, auto/biographies, on historical as well as contemporary problems, and enriching the literature every day. Although no literature is said to have been written in Kosli/Sambalpuri language till the late 19th century, we find the oldest sample of Kosli words, phrases and morphological features in ancient Charyapadas,[20] which are considered to be the oldest form of Oriya, Bengali and Maithili. Nevertheless, the first writing in the language is said to have been penned in 1891 in the first weekly magazine of the region called Sambalpur Hiteisini,[21] which was published under the patronage of Bamanda King Raja Sudhala Dev and edited by Pandit Nilamani Vidyaratna. It was titled ‘Sambalpur Anchalar Prachin Kabita’ written by Madhusudan.[22] Since then, the list of Kosli writings did not stop. For the period from 1891 to India’s independence in 1947, Panda has collected a total of 64 poems written by 35 poets.[23] In terms of the evolution and development of Kosli language and literature, the period up to 1891 is said to be the ‘dark age’, from 1891 to 1970 can be termed as the ‘infant age’, as there were literature written but they could not withstand their counterparts and did not bring about an assertion of their unique identity. It was only after the 1970s that the writings were not only prominent but the writers realized themselves of their unique position coming from a region which had rich cultural heritage but had been marginalized and stigmatized by the powerful coastal Odias. Some of them even gave up writing in Odia language as a protest and wrote in Kosli language, their own mother tongue, till their last breathe. Since long, there have been volumes written about the distinctive nature of the language and its unique identity and status as a language with its own grammar, syntax, phonetics etc. Almost all the classic epics such as the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, Upanishada etc. have already been translated into Kosli-Sambalpuri language. And by now, there are already a few Dictionaries of Kosli-Sambalpuri words to Odia words[24], which shows how unique and distinct both are from each other.[25]

Here it might be useful to list some of the pioneers of Kosli language and literature and their contributions which have been enlightening the leaders and activists of the Kosal movement over the period. They are:

Satyanarayan Bohidar (1913-1980): He is regarded as the father of Kosli-Sambalpuri literature. He established and fortified the identity of Kosli/Sambalpuri language and literature. His poetic excellence lies in his use of pure Kosli/Sambalpuri words which create a magical feeling in the heart of the readers. His major works have been Sripanchami, Ghubukudu, Jikcharana. Although he was a Sanskrit teacher by profession, he dedicated himself to the service of his mother tongue. He also wrote a small booklet on Sambalpuri grammar, which was the first attempt of its kind. The total collection of his writings have been brought out in a single volume Satyanarayan Granthavali published in 2001.

Khageswar Seth (1906-1987): Seth did not have any formal education but learnt his lessons of life from his home and the life around him. He was a born poet and his vision of the world was self-determined. Due to degradation of society around him, he raised his voice against intolerance and inequality in his writings. His notable works were Parchha Sati, Vote Vichar, Papar Maa Baap etc.

Prayag Dutta Joshi (1913-1996): A well-known name in Kosli language, literature and movement, he was the first serious scholar who attempted a linguistic study of Kosli language. In fact, it was Joshi, who so emphatically announced that the language of the region was not Odia, but Kosli. Till his death he was not only producing seminal essays on uniqueness of Kosli Bhasa and literature but also promoted many amateur Kosli writers and poets. He was also among those who for the first time in 1986, submitted a memorandum to the President of India to include Kosli under Eighth Schedule. His small booklet Koshali Bhasar Samkhipta Parichay is considered as a sacred text by Kosli writers as well as leaders of the Kosal movement.

Nilamadhab Panigrahi (1919-2012) A dedicated scholar, critic and poet in Kosli/Sambalpuri language aas well as a prominent and established Odia writer. He devoted wholeheartedly to the cause of Sambalpuri language and literature and is said to have brought about literary revolution in the region. He is best known for his monumental work Mahabharata Katha in six volumes as translations of original Sanskrit verse of Vyasadeva.

Hema Chandra Acharya (1923-2009) A major poet and short story writer, he used to write equally in Kosli/Sambalpuri as well as in Odia. He used pure folk language and gave sincere tone to his creations. His works revolved around rural world in around his own village. He is known for his Kosli Ramayan and is known as Kosli Valmiki.

Mangulu Charan Biswal (1935-) Since 1950s, he has been writing both in Odia and in Kosli/Sambalpuri . He is a well-established poet, story writer, playwright, and lyricist. He is very unique in his word order simple but very effective and heart touching. Though he wrote many plays such as Udla patar Budla Danga, Bhutiar Hatiar, Ulgulan and Sundar Sai, his drama Bhukha (The Hungry Man) which was also made out to a movie, brought his name and fame internationally.

Haladhar Nag (1950-) Born and brought up as an orphan in his maternal uncle’s village, he is hardly a literate to be called as such. Despite his poverty, hardships and sufferings, he has produced volumes of poems which are very popular, powerful and heart touching. He is a born poet, who came to the limelight only during 1990s with his first poem Dhodo Bargachh i.e., the giant banyan tree of the village. A collected volume of his poems have already been published as Lokakabi Haladhar Granthabali (2014) and also a bi-lingual (Kosli along with its English translation) volume of his poems have been available by now entitled Kavyanjali (2016). His poems directly come from his heart and he can recite his poems for hours without even a single word written in paper. Today his voice is considered to be the voice of the entire region. He has been recognized all over the country and several researchers have already been awarded with degrees for their theses on such a unique poet our time.

Dola Gobind Bishi (1960 -) is perhaps the most prominent name today as was in yesteryears, when we look at the movement with regard to promotion and protection of Kosli languagage, literature and culture. Dr. Bishi, in fact, represents the first generation of writers, activists and researchers of Kosli language, literature and culture as well as the bridge to so many generations of writers, poets and researchers on these issues. He was among the first, along with Kosal Ratna Pandit Prayag Dutta Joshi, to announce and to initiate a public discourse on the distinction between languages spoken by the people of coastal Odisha and that of western Odisha, sometime in the late seventies of the last century. During our interview, he was so spirited about sharing some of the historic moments of launching Kosli language movement as a young college going student amidst some old octogenarian leaders such as Kosal Ratna Pandit Prayag Dutta Joshi. He was too realistic to say how the language taught at schools and colleges was so different from the language spoken at home and had hardly any correspondence with each other. And it was with such a realization that he jumped into the fray in searching for the way out of such a conundrum. And no sooner his radical writings on the issue opened up debates and discussions not only in the region but also got extreme reactions from people from coastal Odisha including threat to his life. Nevertheless, he dedicated himself to the cause of his Mother land and Mother tongue, which continues even today. Since 1978, even as a student, he published, perhaps the first Kosli magazine Kosal Shree and urged for recognition of Kosli as a distinct language in itself and not as an appendage of Odia language, which had been neglected, marginalized and stigmatized till then. In 1984 he published a full fledged book on unique grammar of Kosli language Kosli Bhasa Sundri and fought tooth and nail to assert distinctive identity of Kosli people and their language. And to get official recognition of the same, he led a delegation to the President of India in 1986 for inclusion of Kosli language in the Eighth Schedule of India’s Constitution. Not only this, he established a Kosli Sahitya Academy called Kosalayana so as to promote research and publication on Kosli language and culture. And with his initiative such historic books were published and came to our limelight such as Pandit Prayag Dutta Joshi’s Kosli Bhasar Samkhipta Parichaya, which is treated as the nerve of Kosal movement today and Indra Mani Sahu’s Kosli Ramayan. His writings on the language, literature and culture of western Odisha goes into thousands. But some of his historic contributions are: Kosalara Aitihasika Prusthabhumi, which analyzes the historical mooring of western Odisha from the ancient times and gives the historical background of today’s Kosal movement. The other one is Prachina Bharatara Mahajanapada Kosal, which tries to map out the historical location of western Odisha from the ancient period and ascertains that the present day western Odisha, along with parts of present day Chhattisgarh constituted, once upon a time the Kosal state, which has been listed among the sixteen (16) Mahajanapadas of ancient India.[26] In addition to his incisive writings, he has been a source of inspiration to so many generations of researchers and activists dealing with problems of western Odisha in general and Kosli history, language, literature, culture and movement in particular.

Saket Sreebhusan Sahu (1978-) is a very young, energetic and vibrant Kosli poet, writer, playwright, editor, organizer and activist of Kosli language, literature and culture. He is one of the most active leaders of Kosli language movement in recent time. The literary career of Sahu[27] is said to have started when he was in class seventh when he wrote a poem ‘Chasi Bhai’ for the wall magazine of his school and which was also being published in Hirakhand, a premier daily of the region. From his school days, he started participating in Kosli plays and also wrote stories as well as directed Kosli plays such as Bhanga Darpan, Sapan R Samadhi, Akasar Dak, etc. Later on due to his love for his land, language and culture, he actively subscribed to e-groups such as Kosal Discussion and Development Forum (KDDF) and contributed significantly by writing very forcefully on various issues related to Kosli language, literature, culture including the movement for a separate Kosal state. Since January 2010, he has been regularly publishing Beni, a monthly Kosli magazine. Moreover, he has also published a volume on the history of Kosli language and literature titled Kosli Sahityar Itihas (2017) from his own publication house Beni. Not only this, but he has been in the forefront of leading delegations for submitting memorandum to concerned authorities both in the state as well as in the Centre for inclusion of Kosli-Sambalpuri language in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution and has been mobilizing individuals and institutions all over the country with regard to officially recognizing such neglected and marginalized languages. Mention may here be made of, for instance, the Chennai Declaration, which was declared on the sidelines of ‘Language Rights Conference’ held in Chennai on 20th September 2015, and the Campaign for Language Equality and Rights (CLEAR) which has been demanding for promotion of linguistic Rights and Equality and celebration of Mother Tongue Day on 21st February following International Mother Language Day. As a consequence, we can see that for the last couple of years there have been celebrations of ‘Kosli Matrubhasa Divas’ i.e., Kosli Mother Tongue Day, where debates, discussions, essay competitions, poetry recitations are organized so as to bring out Kosli consciousness among the people of the region. Needless to mention that it is due to his initiative that a dedicated school called Haladhar Abasik Banavidyalaya was opened in Kudopali, wherein teaching and learning is done purely in Kosli language. For this, he has also written a few introductory Kosli books for children such as ‘Asa Kosli Sikhma’ and ‘ Asare Pile Kathani Kahema’ and believes that if education is not imparted in one’s mother tongue, it is nothing less than a crime of denying these children their education.

There are several other poets, writers, playwrights, dramatists who are contributing in their unique ways to feed in Kosli literature and Kosal movement. During my field work and also while talking to leaders, activists and scholars of Kosal language and literature I came to know more than hundred magazines, journals, weeklies etc. which have been published over the period for promotion of Kosli language, literature as well as the movement.[28] However, pity to note that hardly they come out regularly and many of them have already become history by themselves. Some are still struggling and reviving gradually. However, what I came to see during my discussion with people in the street that these literatures are not easily available. Neither is any arrangement to record and document these historical write-ups which may uncover the layers that constitute history of the Kosal language, literature and movement. There is also an apprehension about learning and teaching Kosli language and literature, given that outside their private lives, it has hardly any market value. Despite this, however, I came to know that Sambalpur University has been offering a Diploma Certificate course in Sambalpuri-Kosli language and literature for some years by now.

As it stands today, there is both resistance to such a claim as well as recognizing the true essence of the logic of considering Kosli-Sambalpuri as an independent language in itself. It is, therefore, no strange to see that linguists and literary leaders from coastal Odisha are fighting tooth and nail to stop the government from including Kosli-Sambalpuri as a part of the 8th schedule, whereas no wonder to see that there are organizations , institutions and forums to discuss and spread the language and literature of the region. The Government of Odisha has also recognized the value of such a language and literature and already awarding the writers and poets coming from this language. In fact, one of the most popular and prominent writers of this language is Haldhar Nag[29] is very noteworthy who has been recognized for his writings and has already been awarded by Odisha Sahitya Akademi in 2014 and Padma Shri, one of the highest civilian award of the country, by the President of India for the year 2016. And as a consequence of such a popularity of Mr. Nag, the Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik not only invited him to felicitate for his recognition but went a step further and has already announced for establishing a Kosli Language and Literature Research Centre at Bargarh to be named after him so as to promote his language and literature.[30]

Kosli Culture and Kosli Identity

As regards culture and cultural identity of western Odisha is concerned, it still remains to be well-recorded and documented, although the region inhabits a heterogenous population comprising many dozens of castes, tribes and other socio-cultural communities. Given the diversities of its population dominated as it is by tribals, Dalits and several peasant and marginalized communities, the cultural ethos of the region is also a conglomeration of several strands of cultural patterns and traditions. Some of them are considered to be part of great traditions, some of little tradition while some others may be considered tribal tradition or peasant tradition. However, despite these diversities, the people of the region have been known for having come together as a unique cultural community vis-à-vis their coastal ‘others’ and as a consequence they come together as a collective and forge their solidarity, while celebrating their lives. Thus, in the following few pages, we attempt to discuss some major forms of cultural pattern, which are reflected in the festivals, songs, music, dances, rituals, beliefs, their food pattern, traditional artifacts, folk games, folk performances etc., which represent their collective identity as being and belonging to a distinctive region, which the leaders of the Koshal movement are trying to anchor upon and mobilize people along cultural questions such that they are now feeling proud of their culture and promoting it not only in the region but exhibiting all over the country and also outside. This seems to be watershed in the cultural history of the region, given that their culture was once looked down upon, stigmatized and laughed at for being underdeveloped, backward and uncivilized by their coastal counterparts.

We highlight some of the major festivals of western Odisha. Of all the festivals celebrated by people in western Odisha, Nuakhai stands out for wherever one might be, it is during this festival that everybody comes to one’s native place and celebrate with one’s kith and kin. Usually it is on the 5th day of Bhudo (August-September) that this festival is celebrated. Villagers and also people in towns and cities always look forward to this day. It is, by and large, a peasant festival celebrating the first harvesting of paddy which is offered to the deities and then accepted by all as the blessings of goddess Lakshmi. Earlier, Nuakhai was celebrated by people in different dates. However, today we see a common date being fixed for the celebration as a matter of their unity and to conform to their solidarity. In fact, the leaders of Koshal movement and their activists and supporters all over the world—from Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Bhopal, Hyderabad, and Ahmedabad to Los Angeles, California and Dubai– have been using this festival to mobilize people and showcase their strength by celebrating Nuakhai Bhetghats. They call themselves Juhar parivar belonging to a common family despite all their differences. So today, wherever one goes from western Odisha, one can be a part of these parivars and celebrate one’s culture in a homely manner far from one’s home.

The second most popular festival of the region is Puspuni. It is observed through out western Odisha on the full moon day of the month of Pausa (December-January). This is the time when harvesting is completed and hence, people enjoy themselves by meeting each other and celebrating together. Various kinds of food including special kinds of cakes are prepared in every household which is exchanged with one’s friends and relatives.

Rath Jatra is observed on the second day of the bright fortnight in the month of Asadh (June-July) throughout western part of Odisha as that of coastal Odisha. However, they claim that it is their own god which had its origin in their part of Odisha, which was later on took away by the rulers of coastal Odisha. Even in the remotest of villages, people—old and children, men and women look forward eagerly to celebrate it by pulling the chariots of three idols of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. It is the time to refurnish all their homes and get new clothes for all and with sweet food.

Dasra, Buel Jatra and Chhatar Jatra: The festival of Dasra which starts with the first day of the bright fortnight of Ashwin (September-October) celebrates goddess Durga. But more than anything, it is the Buel jatra and Chhatar jatra, which is unique to western Odisha. Buel jatra is a festival of tantra, which has been said to be the greatest contribution of the region to Indian culture.[31] On that day, amid magical chanting the transmigration of the divine soul of goddess is practiced on a man. This man, so possessed, moves round the village from door to door and people worship him as a symbol of the goddess. Chhatar Jatra is observed particularly at Bhawanipatana’s Manikeswari temple. The holy umbrella of the goddess moves from one place to another where thousands of devotees assemble to witness the procession. The large-scale sacrifice of animals to propitiate the goddess, however, creates an unusual scene.

Mention should also be made of Khandabasa festival, which is observed on the eighth day of the dark fortnight of Dasara, especially in the villages where Shakti cult is prevalent. Particularly, in the temple of Lankeshwari of Junagarh, Kalahandi district, a grand festival is observed during which the King of Kalahandi brings the sword of the deity with all her ornaments and attire from his palace in Bhawanipatna. It is also from this festival day onwards that the well-known performance of Ghumura starts and is played all over the region, moving from one village to another.

Dhanu Jatra of Bargarh is based on the story of Lord Krishna and the killing of demon king Kansa. During Dhanu jatra the whole of Bargarh town becomes an open theatre where lilas or activities of Lord Krishna beginning from his childhood to his slaying of Kansa are enacted by real life characters for about a fortnight during Pausa (December-January). Finally, on the last day, the demon king is killed by Krishna representing the victory of good over bad. The jatra also includes various exhibitions, road shows, local music, dances and performances and also gives some relevant social messages on each day of the jatra.

Like Dhanu jatra, people in Sundargarh district celebrate Chaitra Jatra based on the life of Lord Ram. It begins with the day of Ram Navami, when Lord Ram was born and continues for more than a week and ends with Lord Ram ascending the throne of Ayodhya after killing Ravan. It also shows the victory of good over bad which is celebrated with local music, dances, fairs etc.

Lok Mahotsavs: For quite so many years, what we have come across is organization of Lok Mahotsavs by almost all the districts in the region. These Mahotsavs are an occasion to showcase the rich culture and unique tradition of the concerned district. They are well-planned, well in advance. Many local traditions which were almost neglected or on the verge of dying are now given a new lease of life. Seminars, workshops, poetry recitations, various competitions are organized during the Mahotsav. It is also in these Mahotsavs that leaders and activists of koshal movement are seen to be more prominent and trying to mobilize people so as to actively participate in the movement for the sake of their culture and their Mother land.

There are many more festivals which are celebrated throughout the nook and corner of the region full of its sacred calendar. What is interesting to note is that the activists and leaders of Koshal movement are using many of these festivals to awaken consciousness among the masses about their rich culture and how it should be promoted and protected by them. They argue that it would not be sensible any more to look down upon their culture which the people of coastal Odisha had treated them in a very humiliating manner for so long and that it is time to appreciate one’s own culture and tradition.

Given this, it is akin to say that the mobilization on the part of leaders and activists of the Koshal movement is complementary to the development and growth of Kosli language, literature and culture and vice–versa. While mapping the historical landmarks, archaeological antiquities and sacred sites in the region, we come across a rich stock of various strands, some even dating back to pre-historic times in traces, ruins and extant in different stages of preservation. Mention may be made of Paleolithic rock art of Gudahandi cave and Neolithic ones of Yogimath and Dumerbahal in Kalahandi and Nuapada districts and Vikramkhol rock paintings in Jharsuguda.[32] However, no proper study has yet been done to decipher them and they are gradually getting destroyed due to natural calamities as well as man-made disasters. There is a vast corpus of materials including inscriptions on stones and copper plates, coins etc. of different ruling dynasties,[33] and their proper studies may throw new light on the detailed history of the region. While doing my field work especially in Kansil,[34] Ranipur-Jharial[35], and Kosaleswar temple Baidyanath,[36] what we came across is a serious neglect of various historical heritage of the region such that either the State Archaeological Department is not recognizing their historical value or even if it has taken over them, they are not taking proper preservation and security of these monuments. In fact, there have been appeals by people at large and history lovers in particular, to apprise of the sorry state of affairs in this regard to respectable authorities. And many voice in unison that this is nothing but due to ‘step-motherly attitude’[37] on the part of the concerned government authorities, who generally come from coastal Odisha. History of Koshala region is seen to have been wrapped in obscurity. And it is to such a rich cultural past that the proponents of the Koshal Movement, asking for a separate state of their own, are anchoring to and striving to preserve, protect and promote their golden past. It is, rather becoming very obvious to see the people of this region increasingly forging their “nationality” and imagining themselves as a “political community”—the citizens of an alternative Koshal state.[38] And today one can see volumes of works being written in Kosli-Sambalpuri language and if one tries to map out the range of folk songs, folk dances, folk dramas, contributions from the region is quite noteworthy. Not only this, but these cultural uniqueness of the region is appreciated not only by the people from western Odisha but, gradually gaining recognition by coastal Odias as well as the wider world. Researchers, activists of the movement and litterateurs and folklorists in general are attempting at their own levels to see a new avatar of western Odisha, which was until recently, stigmatized for its poverty, backwardness and underdevelopment. Thus, it’s time to see how different markers of Kosli identity such as literary, linguistic and cultural representations are increasingly being used by the leaders of the Koshal movement to garner people’s support and to bring all the people of the region to a common platform in the guise of pan-Kosli identity despite their internal differences.

Notes and References

- Dash, Ashok Kumar, 2009, “Sambalpuri (Koshali) Language and Literature at a Glance” in Guru, Giridhari Prasad (ed), West Orissa: Past and Present, Western Odisha Development Council (WODC), Bhubaneswar: 120.

- See ORISSA ACT – 10 OF 2000 “THE WESTERN ORISSA DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL” ACT, 2000, as notified by the Law Department, Government of Orissa, dated 5th December 2000 having been assented to by the Governor of the state on the 27th November 2000. Also see, “WODC at a Glance” vide http://www.wodcodisha.nic.in/frmglance.aspx.

- The original 13 districts of Orissa at the time of States reorganization and the merger of the princely states have been reorganized further due to increased developmental work and to make the administrative machinery more effective and also due to persistent demand by the people in three successive phases. The first phase which was implemented with effect from October 1992 on Gandhi Jayanti Day as per the election manifesto of the then ruling Janata Dal which effected Koraput and Ganjam districts. Koraput was divided into four new districts i.e., Koraput, Rayagada, Malkangiri and Nabarangpur while Ganjam was divided into Ganjam and Gajapati districts. The second and third phases of reorganization which became effective from April 1993 and January 1994 respectively, affected eight districts (without any change, till date, in three districts such as Sundargarh, Keonjhar and Mayurbhanj), thus giving birth finally to as many as 30 new districts in Orissa. Kalahandi district was subdivided with Nuapada as a new district, Balangir gave birth to Subarnapur/Sonepur district, Sambalpur was divided further into Sambalpur, Bargarh, Deogarh, and Jharsuguda, Baleshwar was divided into Baleshwar and Bhadrak districts, Cuttack was divided into Cuttack, Jajpur, Kendrapada and Jagatsinghpur, Puri was divided into Puri, Khurda and Nayagarh districts, Dhenkanal gave birth to Dhenkanal and Angul, and Phulbani was divided into Boudh and Kandhamal as new districts. For details, see Sinha, B.N., 1999, Geography of Orissa, , New Delhi: National Book Trust, third revised edition: 5-10. Also see Kumar, Hemanshu and Rohini Somanathan, 2015, State and District Boundary Changes in India: 1961-2001, Working Paper No. 248, Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics, November,2005.

- See official website of Western Odisha Development Council (WODC) http://www.wodcodisha.nic.in/frmglance.aspx and also their Annual Activity Reports of various years such as 2012-13 and 2013-14.

- See Tylor, E. B., 1871, Primitive Culture London: John Murray, I: 1.

- The concept of the ‘cultural complex’ is grounded in the theory of analytical psychology, which originates with Carl G. Jung’s early work on complex theory, as in The Theory of Psycho-Analysis, 1913/1967. Such an idea emerges as a way of understanding the collective psyche, as it expresses itself in group behaviour and individual psychological experience. Common characteristics of ‘cultural complexes include their unconscious, their resistance to consciousness, their autonomous functioning, their repetitive occurrence in a group ‘s experience from generation to generation, and their tendency to accumulate historical experiences and memory that validate their point of view. For detail elaboration, reference may be made to Singer, Thomas and Samuel Kimbles (eds) 2004, The cultural complex: Contemporary Jungian perspectives on Psyche and Society, London:Brunner-Routledge.

- For the contributions by individuals and institutions of western Odisha during the Odia Language movement and formation of Orissa province, reference may be made to Supakar, Sraddhakar, ‘The Contribution of Sambalpur in the Formation of a separate state of Orissa,’ translated by Satyanarayan Mohapatra, Orissa Review, Information and Public Relations Department, Govt. of Orissa, Bhubaneswar, April 2005, pp. 82-85, Barik, Pabitra Mohan, ‘A Movement for Restoration of Oriya Language,’ Orissa Review, Information and Public Relations Department, Govt. of Orissa, Bhubaneswar, April 2006, pp. 5-6, Acharya, Snigdha, ‘Linguistic Movement of Odisha: A Brief Survey of Historiography’ Odisha Review, Information and Public Relations Department, Govt. of Odisha, Bhubaneswar, April 2016, pp. 27-33, and Pasayat, Chitrasen, ‘1895-1905: A Golden Decade in the History of Odia Language Movement in Sambalpur,’ Odisha Review, Information and Public Relations Department, Govt. of Orissa, Bhubaneswar, April 2012, pp. 39-42.

- See Supakar, Sraddhakar, cit.: 82 and Pasayat, Chitrasen, ibid.: 39.

- See Supakar, Sraddhakar, op. cit.: 82.

- : 82

- As cited in Supakar, Sraddhakar, : 83, Gangadhar Meher’s ‘Appeal of Utkal Bharati’ published in Samablpur Hiteisini of 5th March 1895 is worth noting. Meher lamented: “The mother is fated to remain in exile. We are also fated to become motherless. Whatever is going to happen is fated to happen. But we should not become cowards and keep up with our struggle.” Also, Supakar points out a report from Hirakhand, another monthly journal from the region, how during the census of 1901, one Baikunth Nath Pujhari, who was then working as an Assistant Commissioner, was engaged in government work but during the evening hours and all through the night travelled from village to village and explained to the people how to answer various questions asked to them and particularly to say and write ‘Oriya’ as their mother tongue so that it will pave the way for introduction of Oriya language in the region once again.

- See Mishra, Sripati, 1918, Simla Yatra (Odia), Cuttack: Utkal Sahitya For details refer Mohanty, Bishnu Charan, 2006, Smrutibasi: Biographical Sketches of Illustrious Sons of Western Odisha (Odia), Bhubaneswar: Western Odisha Development Council (WODC), especially ch: 2, pp. 16-18. Also see Supakar, Sraddhakar, op. cit.: 83-84 and Pasayat, Chitrasen, op. cit.: 41-42.

- Gangadhar Meher (9thAugust 1862-4thApril 1924) was a renowned Odia poet of the 19th century, also known as Swabhab Kavi, the Natural Poet, was said to be a literary Midas, who transformed everything into gold by the alchemic touch of his genius. His major works have been Tapaswini, Indumati, Rasa-Ratnakara, Pranaya Ballari etc. A collected volume of his writings has been published as Gangadhara Granthabali, edited by Nagendra Nath Pradhan, 1996, Alisha Bazar, Cuttack: Dharma Grantha Store. He was a born poet of delicate charm and was a prominent leader of the Oriya Language Movement, which subsequently resulted in the formation of Orissa as a separate province.

- Matrubhumi matrubhashare mamata , Ja hrude janami nahi

Taku jadi gyani ganare ganib Agyani rahibe kahin?

- Utkal Union or Utkala Sammilani was established in 1903 by Madhu Sudan Das (1848-1934), who is known as one of the founding fathers of modern Orissa. Its aims and aspirations were to bring all of the Oriya-speaking people into one common platform and to awaken Oriya consciousness and articulate a collective Oriya identity. The efforts made by Madhu Babu and members of the Utkal Union were historic in not only assertion of an autonomous identity but also bringing all Oriya-speaking people under one administration in the form of Orissa province. And it is well documented that about three dozens of people from western Odisha were actively participating in the deliberations of the Union from its very inception, including Gangadhar Meher, Ram Narayan Mishra and many others.

- In fact, many people during my field work brought about a parallel between what is pathetically referred to as the ‘Bangla domination over Odia language, literature and culture’ and what is going on in terms of ‘coastal conspiracy, hegemony and domination’. It may be recalled that during the British period, the Oriya speaking people were divided in three different administrative units such as Bengal, Madras and the Central Provinces as a consequence, the Oriyas became virtually appendages to these administrative divisions and their language Oriya became linguistic minorities in these provinces. As regards the Bengal dominion, the Bengalis occupied many official positions in Orissa as they were educationally advanced people. They not only looked down upon the Oriyas, their language, literature and culture but some Bengali Officers even tried to abolish Oriya language and replace it by Bengli medium of instructions in the schools of Orissa. Especially, one Bengali teacher from Balasore Zilla School named Kantilal Bhattacharya published in 1870 a booklet which was sarcastically titled as Odiya Ekta Swatantra Bhasa noy. He strongly described that Oriya was merely a dialect of Bengali language. Likewise, another notable Bengali scholar Rajendra Lal Mitra despised and insulted Oriyas and their culture. And it is this Oriya-Bangla language debate which subsequently acted as a catalyst for the intellectual movement among the Oriyas and was later on very instrumental in the rise of Oriya nationalism and ultimately a state of their own called Orissa. The people of western Odisha also complain that the people belonging to coastal Odisha look down upon and stigmatize their language, literature and culture. Needless to mention that despite that there are fundamental differences in spoken forms of coastal and western Odisha and despite there being distinctive grammar, syntax, pronunciation etc., the language spoken by about ten million people is denied its language status and merely designated as a dialect of Odia language.

- Efforts have been made by writers and linguists of western Odisha for quite some time to interrogate the question of fundamental difference between Kosli-Sambalpuri language vis-à-vis Odia language. It was Kosal Ratna Pandit Prayag Dutta Joshi, who for the first time, declared the language of western Odisha as being different from that of coastal Odisha and named it as ‘Kosli’ in many his writings since the late 1970s and 1980s which sowed the seed of a literary renaissance in the region by the 1990s and inspired many generations of writers, poets and linguists which continues till date. Reference may be made to Joshi, Prayag Dutta, ‘Utkala sahitya ku Khadial ra abadana’, Asanta Kali, February 1978, ‘Kosali Bhasa’, Girijhara, November 1981, ‘Kosli Bhasa’, Agni Sikha, 1981, ‘Khadial Anchalar Loka Bhasa’, Saptarshi, June 1981, ‘Upabhasa Nuhen’, Dainik Kosal, 17th October 1981, ‘Swatantra Kosli Bhasa’ Dainik Hirakhand, 15th, 17th, 19th and 20th September 1983, ‘Swatantra Kosli Bhasa’, Saptarshi, November 1983 & September 1984, ‘Paschim Odishar Bhasa Kosli’, Hirakhand, Bishuba Milana Smaranika, January 1985, ‘Swatantra Kosli Bhasa’ Saptarshi, March 1988, March-April 1990 and his full fledged book on the issue Kosli Bhasara Samkhipta Parichaya, edited by Dr. Dola Gobinda Bishi and published by Rabi Kiran Swain on behalf of Kosalayana, Kosal Sahitya Academy, Titilagarh, 1991. A very detailed analysis of the issue was also brought to public discourse by Gobinda Chandra Udgata with his article ‘Bhasa Prasanga- Odia and Sambalpuri’, Saptarshi, March 1997. The contributions of Dr. Dola Gobind Bishi is also noteworthy who has been writing as well as speaking on the issue so forcefully in various media and has already brought out a unique grammar book on Kosli language titled Kosli Bhasa Sundari, 1984 and is preparing a multi-volume Thesarus of Kosli words, phrases and idioms. Also there are seminal additions to such a discourse by several others such as Ashok Kumar Das, ‘Sambalpuri (Koshali) Language and Literature at a Glance’, in Guru, Giridhari Prasad (ed), West Orissa: Past and Present, Western Orissa Development Council (WODC), Bhubaneswar, 2009, pp. 120-138, Ashok Kumar Das, ‘Peculiarities of Sambalpuri/Koshali Language in its Morphology’ Surata, souvenir of Nuakhai Bhetghat, Juhar Parivar, New Delhi, 2009, Patel, Kunjaban, A Sambalpuri Phonetic Reader, Menaka Prakashani, Gole Bazar, Sambalpur, undated, Sahu, Saket Sree Bhusan, ‘Kosli: A Distinct Language’, September 17, 2011 available online vide his blog Kosli Sahitya https://koslisahitya.wordpress.com/2011/09/17/kosli-a-distinct-language/, Karmee, Sanjib Kumar, ‘Kosli Language: A Perspective on its Origin, Evolution and Distinction’, available online vide http://www.orissadiary.com/ShowOriyaColumn.asp?id=31000 dated 25th May 2012.

- The Constitutional provisions relating to the Eighth Schedule occur in Articles 344 (1) and 351 of the Constitution. 344(1) provides for the constitution of a Commission by the President on expiration of five years from the commencement of the Constitution and thereafter at the expiration of ten years from such commencement, which shall consist of a Chairman and other members representing the different languages specified in the Eighth Schedule to make recommendations to the President for the progressive use of Hindi for official purposes of the Union. Art. 351 provides that it shall be the duty of the Union to promote the spread of Hindi language to develop it so that it may serve as a medium of expression for all the elements of the composite culture of India….Initially there were only 14 languages included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution. Sindhi language was added in 1967. Thereafter, three more languages Konkani, Manipuri and Nepali were included in 1992. In 2004 four more languages such as Bodo, Dogri, Maithili and Santhali were added to the list totaling as of today to be 22 languages under the Eighth Schedule. However, it is to be noted that there have been demands for inclusion of 38 more languages in the Schedule which also include the Sambalpuri/Kosali language spoken by the people of western Odisha, which is under consideration by a Committee under the Chairmanship of Shri Sitakant Mohapatra and the Ministry of Home Affairs. During my field work and while interviewing Dr. Dola Gobind Bishi, Lecturer in Odia, D.A.V college Titilagarh, I came to know that it was way back in 1986 that Dr. Bishi along with Koshal Ratna Sri Prayag Dutta Joshi from Khariar had submitted the first memorandum to the President of India to include Kosli language in the Eighth Schedule. Over the period, there have been many more memoranda submitted by various individuals and institutions from the region for this. Although initially inclusion of a language in the Schedule meant that the language would be one of the bases that would be drawn upon to enrich Hindi, today, the list has acquired more significance.

- See Pattanayak, Debi Prasanna, ‘Govt’s Eight Schedule move reflects immature vision’, The Telegraph, Calcutta, 6th March 2014. He originally wrote his reactionary piece called ‘ Matrubhasha O Manaka Bhasha’ on 22nd July 2011 in Sambad, an Odia daily. Following this, there were several rejoinders and reactionary debates between the champions of Kosli language and literature vis-à-vis coastal Odias who saw it as divisive, parochial and suicidal. Some of the outstanding contributions in this context were, for instance, by Sanjib Karmee, Saket Sreebhusan Sahu, Narendra Kumar Mohanty, Arjun Purohit , Sapan Mishra and many others. For details as well as comments, see Kosal Discussion and Development Forum, ‘The Sambad (Odia daily) on our discussion of Kosli language vide https://kddfonline.com/2011/07/22/the-sambad-odia-daily-on -our-discussion-of-kosli-language.

- Charyapadas are a collection mystical poems belonging to the period 8th-12th century with regard to the Vajrayana Buddhism and the tantric tradition in eastern India. For details see Sahu, Saket Sreebhusan, 2017, Kosali Sahityara Itihas, Beni Publications: 4-7.

- The Sambalpur Hiteisini alias the Sumbulpur Patriot is said to be the oldest weekly of not only Sambalpur district, but also of the entire western Odisha region. It is said to have been published by the king of Bamra State since 30th May 1887 so as to bring out consciousness among the Odia-speaking people and to draw the attention of the British administration regarding the problems of Hindi language which was imposed upon them and to introduce Odia as the official language in Sambalpur. However, it was only in the 1891 issue of the weekly that one comes across the writing in Sambalpuri-Kosli language for the first time.

- See Panda, Sasanka Sekhar, 2003, Jhulpul, Cuttack: Chitrotpala publications: 7.

- Ibid: 1-2.

- Tripathy, Prafulla Kumar’s compiled book Samalpuri Oriya Shabdakosha (1987), i.e., a Sambalpuri to Oriya Dictionary, and Guru, Narasingha Prasad, 2016, Koshali-Odia Abhidhan Tikarpada, Balangir: Binapani Prakashan. Also, during my interview with Dr. Dola Gobind Bishi, a well-known writer and researcher of Kosli language, literature and culture in Titilagarh pointed out that he is preparing a multi-volume series on Kosli Thesarus, which would not only collate unique Kosli words, phrases and idioms but will also illustrate their historical roots, contemporary usages and their comparative analysis vis-à-vis Odia terms.

- The uniqueness and distinctive identity of Kosli and Odia languages are debated throughout the history although it is said to have been unnecessarily stretched too far. Some researchers, activists and proponents of the Kosal movement have been trying to go to the root of these languages and suggesting that Kosli is an ancient, rich and sweet language. It belongs to Indo-Aryan family of languages. Legend is that the original Shouraseni Prakrit was travelling towards East and before becoming Magadhi, it stopped in Kosal region and evolved a form. As it evolved on the way to Magadh, it is also known as Ardha-Magadhi. On the other hand, Odia language is said to have come from Odra-Magadhi Prakrut although it also belongs to Indo-Aryan family of languages. For detailssee Sahu, Saket Sreebhusan, ‘Kosali Language: A Reflection of Regional Disparity in Odisha’, vide https://odishawatch.in/kosali-language-reflection-disparity-odisha/. Also see Joshi, Prayag Dutta, Kosali Bhasara Samkhipta Itihas, edited by Dolagobind Bishi, Beni publications, second edition, 2013: 24.

- Mahajanapada literally means a great country. The political division of ancient India during 6th to 4th century BC mentions Sodasha Mahajanapadase., sixteen (16) great kingdoms such as Anga, Assaka, Avanti, Chedi, Gandhara, Kashi, Kamboja, Kuru, Kosala, Magadha, Malla, Matsya, Panchala, Surasena, Vriji and Vatsa.

- Refer ‘The Profile of a good Young Writer Saket Sreebhusan Sahu’, available online vide http://eodisha.org/the-profile-of-a-good-young-kosli-language-writer-saket-sreebhusan-sahu/ dated 11th December 2012.

- A list of Kosli language magazines have been available online compiled by Sapan Mishra, Sambalpur University which has been approved and produced by Kosal Discussion and Development Forum (KDDF). Arranged alphabetically, it lists in total seventy seven (77) Kosli magazines. For details, see ‘A Complete List of Kosli Language Magazines’ vide http://kddfonline.com/. However, while I was doing my fieldwork in the region and was looking for these magazines, I could hardly collect any of these magazines. I also came across a few more new magazines which were not in the list. While talking to some of the editors of these magazines and journals, we came to realize that the major problem in the production and marketing of such magazines are due to the problem of readership and due to lack of financial viability. Dola Gobind Bishi, for instance, was one of the earliest to publish a magazine called Kosal Shree during his student days in 1978. However, he complained during our interview that there is hardly any profit that they got in return even to publish the second issue. Such endeavours, he lamented, were carried on by the spirited persons and activists with good intention, but without any capitalistic market oriented calculations. As a result, whatever is published is privately circulated like charity and it is pity to note that after sometime even the writers, publishers and printers would be unable to find a copy of the same for themselves.

- Haldhar Nag was born on 31st March 1950 in Ghens, Bargarh District, his maternal uncle’s village. He grew as an orphan from his very childhood, who survived by washing plates in a hotel, selling peanuts on the street and is hardly literate. But today he represents a powerful voice of the entire western Odisha and its identity. He has been bestowed with the Kosal Ratna award, recognizing him as a jewel of the region. His poems are true reflection of the everyday life of the common men and women of the region. He is considered as the messiah of the toiling millions for he fights for the oppressed and the marginalized through his poems. He is also popularly known as Lok Kabi., People’s Poet and Kosli kuili i.e., koel or cuckoo bird for his enchanting poetries. People consider him as the second Ganga Dhar Meher, and by now, about half-a-dozen researchers have already done M. Phil / Ph. D theses on him and many more are still researching on him and his writings. See especially Mohan, E. Kiran, ‘Poet Haldhar Nag: An Agent of Social Reform’, Orissadiary.com, 17th November, 2015, Guru, Sudeep Kumar, ‘Poetry makes him known as new Gangadhar Meher, Peanut seller Haladhar Nag carves niche for himself as poet of Kosli language’, The Telegraph, Calcutta, 25th September, 2010 and Krishnan, Madhuvanti S., ‘Poetic Crusader’, The Hindu, 13th April, 2016.

- See Sanjib Karmee, ‘Naveen Babu announces a Kosli Language and Literature Research Centre at Bargarh’, Kosal Discussion and Development Forum (KDDF) vide https://kddfonline.com/2016/04/07.

- See for details, Deo, J.P.S, 2010, ‘Yogini cult is the gift of Bolangir district to Indian culture’, in Udgata, Srinivas et.al (eds), Cultural Legacy of Western Odisha: A Commemorative volume in Honour of Late C Rath, published by Koshal Nagar, Bolangir: P. C Rath Memorial Trust: 71-82.

- For details, see Mishra, Dadhi Baman, 2009, “Archaeological Heritage of West Orissa”, in Guru, Giridhari Prasad (ed), West Orissa: Past and Present Bhubaneswar: Western Orissa Development Council: 26.

- Ibid: 27

- Kansil is a small village of about 1500 population living in 325 houses (according to 2011 census) in Bangomunda Block of Balangir District. This village has been supposedly once the capital city of Kosal King Kusha named ‘Kushasthali’ or ‘Kushawati’. I came across the name of the village in some vernacular writings and also writings by some noted historians such as Ramachandra Mallick (1867-1936), perhaps the earliest historian of the region with his Sankhipta Koshal-Patana Itihas (1931: 46-48, 62), wherein he emphatically proves that this village along with its neighbouring villages such as Ranipur, Jharial, Bahabal and Balkhamar constituted five units of the ancient Koshal Nagar with specialized tasks such as Queen’s Palace, Bathing Ghats, Reserved Force and Storage of wealth and property respectively. Purna Chandra Rath (1909-1952), is another noted historian from the region, who devoted one full chapter on the village called “Kansil’ (2014: 108-111) with details of historical and archaeological sites in and around the village and ascertains without any doubt, how this village, once upon a time, was a well-developed town / nagari, and that the present-day name of the village Kansil is nothing but a corrupted version of the ancient Kosal Nagar or Kushasthali. Sadananda Agrawal (1952-2017), whose contributions in analyzing, interpreting and popularizing Koshal history is quite noteworthy and especially his Koshala Itihas (2013: 21) establishes with archaeological evidences that the village and the entire region especially the historic Ranipur-Jharial temples represents a very unique architectural style which is possible only in the case of a highly developed kingdom and civilization. Also, while talking to some prominent leaders of the Koshal movement such as Nataraj Mahapatra, Khariar during my field work, I could realize the significance of the village for uncovering the history of the entire Koshal region and therefore, went to the village in March 2017 and saw by myself some ruined structures at several places in and around the village, which are yet to be studied properly. However, while talking to people in the village we saw a common voice by almost all the villagers-old or young, educated or uneducated, men or women—that they are, indeed, so proud of their history as they belong to ‘Kosal Nagar’ or ‘Kausalya Nagar’, once the capital city of Kosala kingdom. They were also very enthusiastic about the prospect of the ‘Koshal Movement’, which they said, will bring back their glorious past. However, they also put forth before me the neglect on the part of the government as regards these historical monuments and requested me if I can do anything in this regard.

- Ranipur and Jharial are twin villages under Titilagarh Sub-Division in Balangir District and bear strong traces of their ancient heritage. The archaeological sites in and around these two villages is known as “Soma Tirtha” in various scriptures pertaining to the reign of Somavamsi kings dating back to 8th-9th There are more than hundred small, medium and large temple structures in different stages of decay and preservation. The unique Hypethral temple of 64 Yoginis is one of the four remaining such shrines such as Hirapur near Bhubaneswar, Khajuraho and Bhedaghat near Jabalpur. It also shows a confluence of Saivism, Vaisnavism, Buddhism and Tantrism. Although this place has already been taken over by the State Archaeology Department and also has been declared as “Monuments of National Importance”, the state of the affair as regards its protection and preservation is far from satisfactory. There is no security guard as such and as a result, many of the structures from the 64 Yogini shrine are already lost. I could even see by myself, some historical rock structures far from the site, probably being taken by someone gradually. The villagers as well as lovers of history of the region lament that had it been situated in the coastal part of Orissa such as Puri or Bhubaneswar, the situation could have been very different and the place could have been developed properly and not as it is today.

- The Kosaleswar temple at Baidyanath is on the bank of river Tel, situated about 15 Kilo Meters to the South-East of Sonpur in Subarnapur District. Historian N. K. Sahu has been of the opinion that the temple was constructed during the reign of Telugu-Chodas in the last part of 11th or 12th century A.D. There is also a reference in one copper plate record that Baidyanath urf Kosaleswar was the tutelary deity of the Telugu-Choda ruling family. There are some who on the basis of the architecture, sculptures and especially the specimens of plastic art, date it back to 7th century AD or even earlier. Charles Fabri (1899-1968), the English curator and Buddhist doctor opines that it was originally a Buddhist structure which has been refurnished later on by the Hindus as per their need. Sadananda Agrawal (1952-2017), a crusader of Koshala history suggests it to be of around 9th century A.D and has also appealed several times to the concerned archaeological Department of the state for its protection and preservation. When I visited the temple in March 2017, I was aghast to see the sorry state of affair of such a historical monument of the region. The main temple was supposedly under repairing and all the statues of varying gods and goddesses were found to be scattered all over and were left unattended and unprotected lying outside the temple in a far corner. While talking to the villagers, came to know that originally, there were three temples in the precincts but today there exist only two temples because one temple on the bank of the river was taken away by the flood water in 1967, and only a few stones stand there today.

- Such a phrase or idiom is popularly used throughout India and also outside so as to refer to the problem of neglect, disregard or inattention. It also underlines the ill treatment meted out by one’s literal relatives—the step/foster father or mother, who are not real biological parents and are stereotyped of being bad father or mother, who do not take care of their foster children at par with their ‘own’ biological children.

- For the discourse on “nation” as an “imagined political community”, see Anderson, Benedict (1983), Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, revised edition: 5-7.

Author’s Details

Tila Kumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi. E-mail: tilasocio@yahoo.com. This article has been published in SOCIAL TRENDS, Journal of the Department of Sociology of North Bengal University, Vol. 5, 31 March 2018; ISSN: 2348-6538, pp. 37-63.