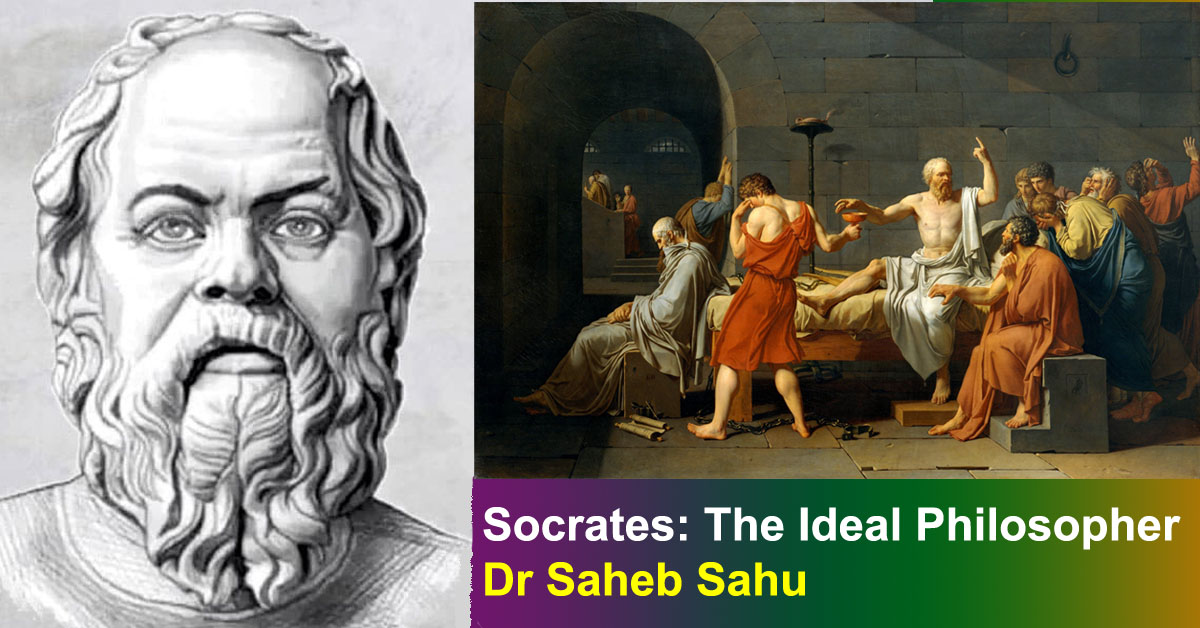

Socrates (470—399 BCE) is my ideal philosopher. He was born in Athens, Greece about 80 years after Buddha (563?—483BCE) died. He lived during the golden era of Greek culture in a city that had become the intellectual and cultural center of the Mediterranean world. Many consider Socrates to be the father of Western philosophy.

We have inherited contradictory pictures of Socrates. Plato (424—348 BCE) his most famous student and other of the dialogues in which Socrates stars, portrays him as the ideal philosopher. Aristophanes (446—386 BCE), in his play The Clouds, pictures him as a buffoon. Socrates describes himself as a sort of gadfly given to the Athenian state by the Gods. By dictionary definition a gadfly is a fly that bites livestock, an annoying person, especially one who provokes others into action by criticism.

His method (the Socratic Method) consisted of asking people questions about matters they personally knew something about. Socrates would usually begin by asking for a definition of a concept like justice. Once a definition was offered, he analyzed its’ meaning and critically examined it. Some defect was found, and the definition was reformulated to avoid the defect. Then this new definition was critically examined until another defect appeared. The process went on as long as Socrates could keep the other parties talking.

Socrates got into trouble with the powerful people of Athens and was brought to trial in 399 BCE. Three Athenians— Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon brought charges against him. The charges were two: impiety against the Gods of Athens and corruption of the youth. There were 501 Athenian citizens on the jury. The Apology, is the Plato’s account of the trial and Socrates’ defense. It provides a dramatic account of why Socrates believed that the pursuit of truth is important for a good life.

The Apology: By Plato*

Some excerpts:

“O men of Athens:

Young men of richer classes, who have little to do, gather around me of their own accord. They like to hear the pretenders examined. They often imitate me and examine others themselves. Then those who are examined by the young men instead of being angry with them are angry with me.

…What do they (Meletus, Anytus and Lycon) say?” Something of this sort: “Socrates is a doer of evil and corrupter of youth, and he does not believe in the Gods of the state. He has other new divinities of his own.”

Meletus: Yes I do.

Socrates: I want you to know if you kill someone like me, you will injure yourselves more than you will kill me…

… If you kill me you will not easily find another like me, who, if I may use such a ludicrous figure of speech, am a sort of gadfly given to the state by the Gods.

… As you will not easily find another like me, I would advise you to spare me.

… My friends, I am a man, and like other men, a creature of flesh and blood and not of wood or stone as Homer (author of the Iliad and the Odyssey)says.

… To you and to the Gods I commit my cause, to be determined by you as is best for you and me.

The Athenian jury returns a guilty verdict and Meletus proposes death as a punishment.

Socrates: There are many reasons why I am not grieved, O men of Athens, at the vote of condemnation. I expected this and only surprised that the votes are so nearly equal (he was found guilty by a margin of 21 votes out 501 votes). Meletus proposes death as penalty. What shall I propose on my part?

… What shall be done to the man who has never been idle during his entire life, but has been careless of what many care about—wealth, family interests, military offices and speaking in the Assembly, and courts, plots and parties?

… I am convinced I never intentionally wronged anyone, although I cannot convince you of that— for we had a short conversation only.

… Someone will say: Yes, Socrates, but can you not hold your tongue, and go into a foreign city (self exile) and no one will interfere with you?

… If I say I cannot hold my tongue, you will not believe I am serious. If I say again that greatest good is daily to converse about virtue, and that the life which is unexamined is not worth living— that you are still less likely to believe. Moreover I do not believe that I deserve any punishment. As I don’t have any money, I propose a fine of one mina (a currency in Ancient Greece at that time). However, my friends Plato, Crito and others are willing to pay a fine of 30 minas on my behalf.

The jury votes again to decide between Socrates’ proposal of a fine and Meletus’s proposal of death penalty. The verdict is death.

Socrates: The difficulty, my friends, is not avoiding death, but avoiding evil; for evil runs faster than death. I am old (He was 70) and move more slowly, and the slower runner has overtaken me. My accusers are keen and quick, and the faster runner, who is evil, has overtaken them.

… Let us reflect in another way, and we shall see there is great reason to hope that death is good. Either death is a state of nothingness and utter unconsciousness, or, as men say, there is a change and migration of soul from this world to another.

… But of death is the journey to another place, and there, as men say, all the dead are, what good, O my friends and judges, can be greater than this?

… Wherefore, O judges, be of good cheer about death, and know this truth— no evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death… I am not angry with my accusers or my condemners. They have done me no harm, although neither of them meant to do me any good; and for this gently I blame them.

Still I have a favor to ask of them. When my sons are grown up, I would ask you, O my friends, to punish them. I would have you trouble them, as I troubled you, if they seem to care about riches, or anything, more than virtue. Or, if they pretend to be something when they are really nothing, then chastise them, as I chastised you, for not caring about what they ought to care, and thinking they are something when they are really nothing. And if you do this, I and my sons will have received justice at your hands. The hour of departure has arrived, and we go on our different ways— I to die, and you to live, which is better only the Gods know.”

Friends, followers and students of Socrates encouraged him to flee from Athens (they had bribed the guards) but Socrates refused. Faithful to his teaching of civil disobedience to the law, the 70-year old Socrates executed his death sentence and drank the hemlock (plant poison) as condemned at trial. The full reasoning behind his refusal to flee is the main topic of the Crito.

Conclusion

Socrates is considered the founding father of Western Philosophy and the first moral and ethical philosopher of Western traditions. Plato was one of his most famous students and Aristotle was a student of Plato. Socrates was not an open atheist even though he was charged as if he was one. He just did not believe that Gods were that important. He was after knowledge. Asking questions, getting an answer and asking more questions were his method of searching for true knowledge. He considered himself as a gadfly (horse fly), an irritant to the authorities. For being true to himself, he was condemned to death. As much as Socrates drank the poison willingly without complaint (having decided against fleeing), R. G. Frey (1978) has suggested that, in truth, Socrates chose to commit suicide.

About 85 years before the death of Socrates, Gautama Buddha on his deathbed told his disciples—“Believe nothing, no matter where you read it or who has said it, not even if I have said it, unless it agrees with your own reason (Be your own lamp) and your own common sense.”

Sources

- Plato’s Apology—Benjamin Jowett’s nineteenth century translation as updated and revised by Chistopher Biffle, A Guide Tour of Five Works by Plato. Mountain View, CA; Mayfidd, 1988, pp30-50

- Wikipedia.org-Nov 10th 2020