On January 26, 2010, when 85-year-old Boa Sr passed away at Port Blair, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, many things died with her. The most important of the cultural heritage that faded into oblivion with her passing away was her language – Bo, of the Great Andamanese family of which she was the last speaker . And with that an endangered language had met its end.

Just a few months before the passing away of Boa Sr and Bo, the Unesco had released an atlas of the world’s endangered languages, which India had topped with 196 languages in the category (Tulu was added to take the number to 197). The figure had set the alarm bells ringing in a linguistically wellendowed country like India. Though work has been going on to save the country’s languages, the issue has come under the spotlight with Google announcing its Endangered Languages Project recently (its website, www.endangeredlanguages .com, lists 53 languages in India’s account).

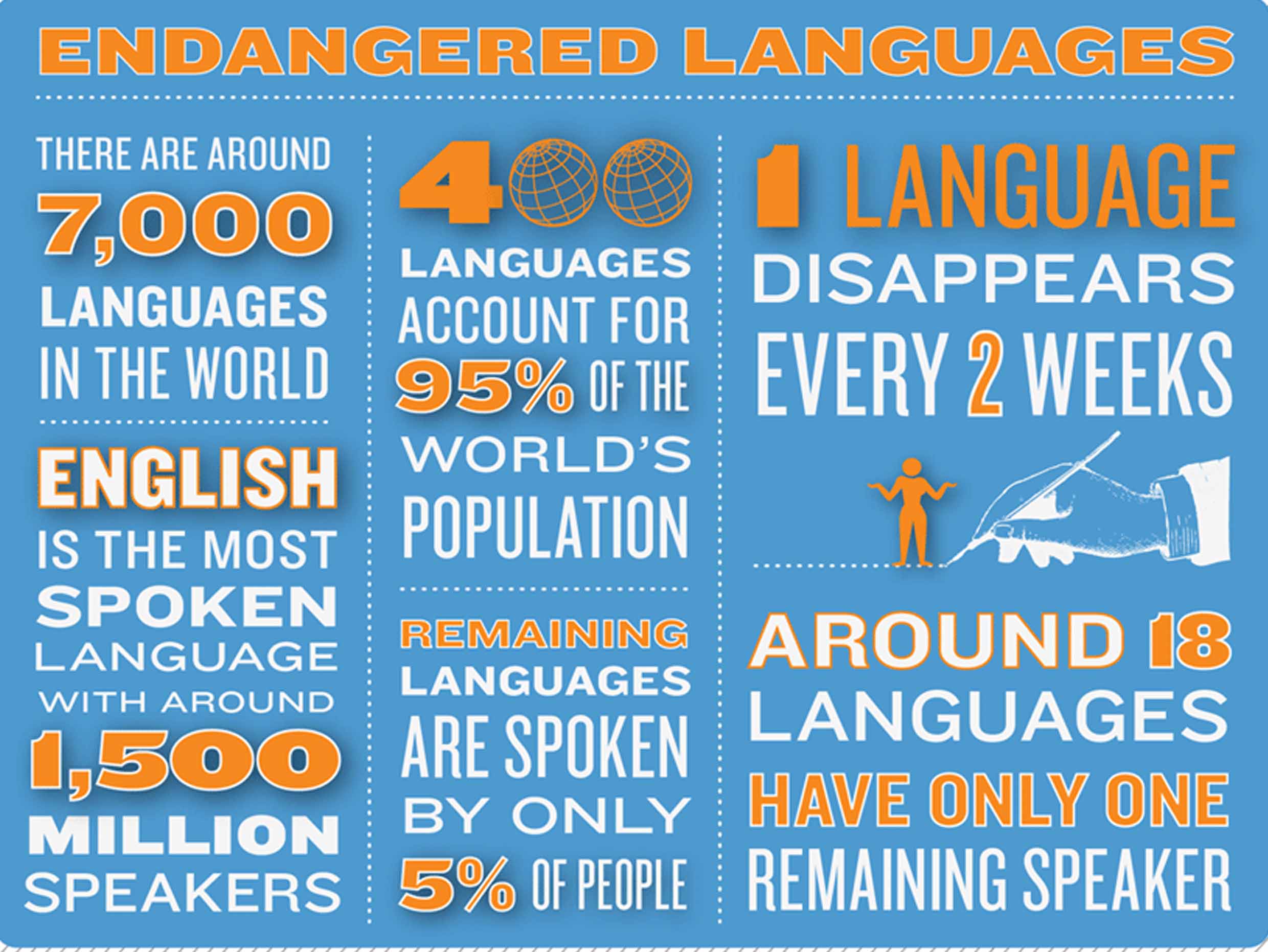

What after all is a dying language and how can it be saved? An endangered language is one that is likely to become extinct in near future. These are languages that are falling out of use with newer generations switching to other languages for various reasons.

S N Barman, director of the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL), Mysore, says, “A language’s survival becomes threatened primarily if it is abandoned by its speakers. People may give up their language for various reasons -for better social identity, upward mobility or for economic reasons. Often, political reasons too play a part though no Indian language has become extinct due to imposition of a state policy.”

As for saving these languages, the community’s interest in safeguarding its linguistic heritage – which implies the language and other cultural symbols of the community enumerated through its language – is cited as the most vital factor by most scholars. A Krishna Murthy, secretary, Sahitya Akademi, says: “The primary issue is not that of the language but of its speakers. If a community and its way of life are preserved, its language will automatically survive. Sindhi, for instance, is a stateless language yet it thrives due to its speakers.”

The Sahitya Akademi supports 24 Indian languages – 2 more than the number recognized by the Constitution – and Murthy adds that support is always available for work being done in any language even if it is unrecognized, or is only a dialect.

The CIIL’s role in saving a language involves surveys to measure its state of endangerment. “If a language’s extinction is imminent, then detailed documentation is undertaken. But if there is scope to save it, then after the documentation , efforts are made to introduce it at the primary level of education ,” says Barman.

The CIIL is soon going to submit a new project to the government on saving endangered languages . Author/poet Ashok Vajpeyi had also suggested the institution of an independent national commission for languages to former prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpeyee with the latter announcing the same on September 14, 1999 but the idea was later shot down. Vajpeyi says that much more is needed to preserve India’s rich linguistic diversity. “As languages are the repositories of the entire racial memory, the communities as well as the state will have to jointly save the languages. Unfortunately, language is not a top political or social issue in India today,” he says.

A new stakeholder on the subject has taken birth with the Google project. Gregory D S Anderson, director of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, Oregon, USA, who has been working in India on tribal languages of the Munda and Tibeto-Burman families for two decades, says, “The internet develops an online presence and allows various communities a level playing field which was inconceivable until recently.” Anderson adds that his organization has been working on various language projects with Indian communities such as the Bonda (Remo), Didey and Sora of Odisha , the Mundas of Jharkhand, the Khasis of Meghalaya and the Koro-Aka of Arunachal Pradesh among others.

According to Endangered languages .com, only 50% of the languages alive today would be spoken by the year 2100 – which means that despite efforts, some languages will eventually die. This also means that the threat of extinction for languages like the Great Andamanese , which has only 5 speakers, is real. After all, except for Hebrew in Israel, no other language in the world has made the enviable transition from being a dead entity to the first language of a large community. But with the world coming together both online and offline, there is hope that the languages would remain with us even when their speakers are gone.

Struggling for survival

The Great Andamanese, spoken in Middle and North Andaman has only 5 speakers while Jarawa in the South Andaman Island has 31 A few languages spoken in northeast India, like Ruga, Tai Nora, Tai Rong and Tangam – have just 100 speakers each.

Archana Khare Ghose (With inputs by Arushi Malhotra)